Talk about Go: The operating system's thread scheduling and Goroutines

Every task running on our computer is resource allocation at the operating system level. From starting a process to creating a thread, with a fixed number of cores, multiple threads execute concurrently.

Foreword

Go goroutine is a more fine-grained resource than system threads, lightweight and easy to switch. I read some related articles in the past few days, this time I try to go from the operating system to the Go goroutine, and briefly talk about them How it is related and my personal understanding.

Basic Concept

Operating System(OS)

The operating system is responsible for the scheduling of the underlying hardware. It allocates CPU, memory, and disk resources, and allocates different threads to execute on different CPU cores to ensure that each program executes as expected. Every program we submit eventually translates into a series of instructions that the operating system recognizes.

Thread

The above converted series of instructions, the operating system will help us execute through threads, in essence, threads are a path of execution, an executable program path.

A thread has the following three states:

- Running:being executed, ideally all threads are in this state

- Ready:it can be switched to running at any time, and that call’s context switching, it requires a certain price.

- Waiting:It needs to wait for resource allocation or IO (network/device) blocking, and it needs to be ready to run. This is the last thing that users want to see, and it has become the performance bottleneck of most programs.

System Scheduler

The scheduler shoulders a huge mission, mainly to schedule the relationship between the CPU and the thread to ensure that no CPU will be idle. Imagine that the CPU is the hamster in the hamster cage. Once the scheduler finds that there are hamsters(CPU) dozing off, just push them to the wheels (thread) and run without stopping for a moment. After all, the computing power of the CPU is very powerful, and one millisecond of idleness is a huge waste.

On a 4-core machine, there are only 4 hamsters (quad cores), which wheel (thread) runs first depends on the priority of the wheel (thread). The scheduler shoulders the mission of strategizing, not only to reduce the delay of urging the hamster to run, but also to ensure that no tasks can be left unexecuted all the time. If the thread has not been processed by the hamster, it is called starvation.

Cooperative/Preemptive

Cooperative and Preemptive is the multitasking operation strategies in the OS. The differences between the two scheduling strategies are as follows:

- Cooperative scheduling: allows tasks to be executed until the task actively informs the scheduler to switch, giving up resources

- Preemptive scheduling: allows tasks to be broken by the scheduler during execution, and the scheduler decides the next task to run

Task Type

Different tasks have different requirements on system resources

-

I/O frequent switching:

IO refers to Input/Output, input and output waiting. This kind of job waiting for resource input/output, the main bottleneck is whether resources are allocated in place, such as system calls/file IO, etc., the thread switching time is far less than the IO device/network delay, and the main shortcoming lies in waiting for I/O /O, instead of thread context switching, so more threads can be allocated to perform pre-combat preparations during the period when the “ammunition” has not been delivered. -

computationally intensive:

This kind of task mainly consumes CPU, such as calculating the Nth bit of pi with a thread. If a large number of threads are allocated to it, the system must not only ensure that each thread shares the computing state, but not consider the occurrence of dirty read/dirty write operations, but also need to perform thread switching frequently, which will cause a lot of waste of time, and the thread restarts every time. Wake up must be in Program Counter to find the location of the next execution instruction. In the case of a fixed number of cores, allocating too many threads will not worth the loss.If your program is focused on CPU-Bound work, then context switches are going to be a performance nightmare. Since the Thead always has work to do, the context switch is stopping that work from progressing.

But in some case, such as Map-Reduce, which refers to first splitting and then aggregation. When your computing task can be divided into many modules, if the different execution order of each module will not affect the final result, try to “break them one by one”, and finally re-converge, if the tasks can be reasonably allocated, multi-threading is definitely an advantage on a single thread.

Let’s try to compare the performance differences between the two in different scenarios by listing a few simple Go programs and processing them through single/multi-coroutines.

Map-Reduce:

This example is relatively simple, our goal is to accumulate an arithmetic sequence

var PIXEL_ARRAY []int

// initialize an arithmetic sequence, and then try to sum it by the single-goroutine/multi-goroutine function for accumulation

func init() {

for i := 1; i <= 100000; i++ {

PIXEL_ARRAY = append(PIXEL_ARRAY, i)

}

}

Later, we use the single-goroutine/multi-goroutine version to distinguish the two implementations

// Single-goroutine brute force version

func SumWithSingle(arr []int) int32 {

var sum int32

for i := 0; i < len(arr); i++ {

sum += int32(arr[i])

}

return sum

}

// Multi-goroutine version

func SumWithMulti(arr []int, gNum int) int32 {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// each goroutine equally calculates the slice interval allocated by itself

wg.Add(gNum)

var sum int32

// average length of each task

div := len(arr) / gNum

for i := 0; i < gNum; i++ {

Left := i * div

Right := Left + div

if i == gNum {

Right = len(arr)

}

go func() {

// separate summarize for each goroutine

ps := 0

for _, value := range arr[Left:Right] {

ps += value

}

atomic.AddInt32(&sum, int32(ps))

wg.Done()

}()

}

// wait for each goroutine to complete the calculation

wg.Wait()

return sum

}

Performance Analysis

import "testing"

var PIXEL_ARRAY []int

func init() {

for i := 1; i <= 100000; i++ {

PIXEL_ARRAY = append(PIXEL_ARRAY, i)

}

}

func BenchmarkSumWithSingle(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

SumWithSingle(PIXEL_ARRAY)

}

}

func BenchmarkSumWithMulti(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

SumWithMulti(PIXEL_ARRAY, 10)

}

}

Output:

On a 4-core computer, start 10 coroutines for concurrent processing. For this example, multi-coroutines are better than single-coroutines, which is as out expectations.

$ GOGC=off go test -run none -bench . -benchtime 3s

goos: windows

goarch: amd64

pkg: HelloGo/basic/Multi

BenchmarkSumWithSingle-4 50000 63583 ns/op

BenchmarkSumWithMulti-4 100000 39216 ns/op

PASS

ok HelloGo/basic/Multi 8.623s

At the operating system level, the execution order of each thread is not guaranteed. In Go, the same goes for coroutines. Taking the previous example as an example, the Map operation of Map-Reduce is to cut the arithmetic sequence, and the execution time of the different Go goroutine allocated to the task is uncertain, it is possible 1+2+3+..., or 21+22+23+...

If the program wants to control the order of execution of the corresponding threads, it needs to add scheduling instructions in the upper layer of the operating system, such as programming languages, such as ++ atomic operations, synchronization locks, mutex ++, and the performance of the program is also related to the granularity of the lock. There is a relationship, and this related knowledge can be used as a future expansion.

The implementation of Go scheduler is based on the concepts of operating system scheduling. Later, we will try to go to a higher level (user mode) and analyze from the perspective of how Go coroutines are scheduled.

Go Scheduler

As we all know, the Go scheduler has the following main components:

- M: Worker thread, created by P and associated with OS thread, can be understood as M is OS thread

- P: Context, the resources required to process the code, the number of creation is related to the number of CPU cores, each P will be allocated an OS thread (M)

- G: The current goroutine, if associated with the OS thread (M), represents the go code that is about to be executed or is being executed. G can find them in two queues, the local/global queue, which we’ll talk about later.

At any time, M goroutines need to be scheduled on N OS threads that runs on at most GOMAXPROCS numbers of processors.

P: the logic CPU core

The P of GO is related to the number of your CPU cores. Note that this is not the real number of CPUs, it is the number of logical CPU. Looking at the task manager, in the case of a 4 core CPU, if your machine has hyperthreading (i7 processor), and each physical core has two threads, then it means that there are logically 8 available in the Go program The number of processors, logical CPU should be 8.

That is, the P mentioned above.

My current machine is (i5 processor), one thread per core, so the number of logical CPUs (P) output below is 4, When multiple threads are started, my machine can at most It supports 4 system threads in parallel, and the extra threads are concurrent. You can see the number of logical P by executing the following Go code on your machine:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"runtime"

)

func main() {

// NumCPU returns the number of logical

// CPUs usable by the current process.

fmt.Println(runtime.NumCPU())

}

Each P will allocate a system thread M, which is equivalent to saying that in the Go program on this machine, I have 4 system threads that can be used to perform my tasks, each of which is Independently linked to one of the cores, P.

M Go coroutines will be allocated on N system threads, each G to be run must be associated with P (logical CPU), the program can interfere with the number of GOMAXPROCS, to control the maximum number of P that can be used.

The following diagram may be more intuitive:

![]()

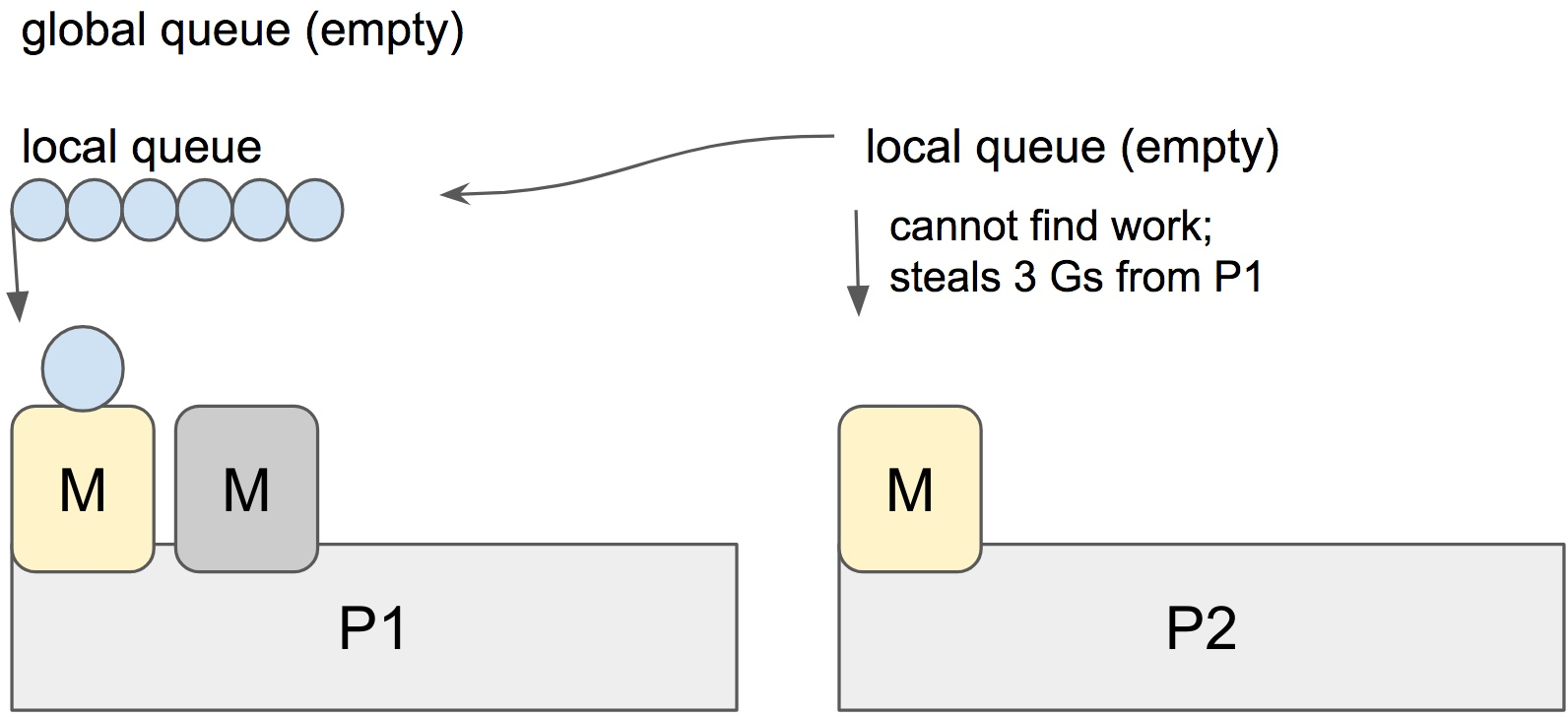

In Go, each context P will allocate a local goroutine queue (LRQ), called **Local Run Queue **, a M must be associated with all The required resources P can run the corresponding G queue, just as each thread queue at the operating system level needs to be allocated and associated with CPU to be executed, just like we mention above, the wheel (M) needs to be driven by the hamster (P) to execute (run the G goroutine task).

As shown below:

![]() P1, P2 are relatively fixed, M and G can be selected with the scheduler allocation.

P1, P2 are relatively fixed, M and G can be selected with the scheduler allocation.

Switching of Go coroutines

After understanding some of the above concepts, now let’s look at Go how to switch the goroutine. As mentioned earlier in the article, if too many threads are created, due to the uncertainty of system scheduling, the threads cannot be executed and may be starved for a long time. In the same way, the Go goroutine will also have the phenomenon of “pulling over”, so the Go scheduler needs some conditions to trigger the goroutine switch, so as to avoid stopping the car and stop starting.

The specific switch it is the disconnection and reconnection between the P-M-G by Go scheduler.

The following scenarios may cause the scheduler to make a decision on the execution context, i.e. the switch of the go goroutine:

- go keyword, create a new goroutine

- garbage collection

- system call

- Synchronization/mutex/

Gosched()etc.

Example

a simple and relatively common example, we try to interfere with the Go scheduler by limiting the number of logical CPUs.

func main() {

// Set at most 1 P can be associated

runtime.GOMAXPROCS(1)

go func() {

for {

// Keep idling

// if there are no other function calls, the goroutine will not switch under a single processor

;

}

}()

runtime.Gosched()

println("main done.")

}

We set the number of logical CPUs for this run through runtime.GOMAXPROCS(1), which means that the available P is only 1, it can only be assigned to one goroutine at most for execution at the same time. If this program is executed, since the main goroutine executes the concession Gosched(), the Go goroutine that has obtained the right to run will be executed. Since the goroutine executes empty statements in an infinite loop, the program will not have any output, and another goroutine does not get the chance to run, so the program will never exit.

Note that this is different from the above runtime.NumCPU(int) method, NumCPU() directly calls the system method at startup, so it will not change after the setting of GOMAXPROCS The original return value of NumCPU(), GOMAXPROCS only limits the number of P at this run time.

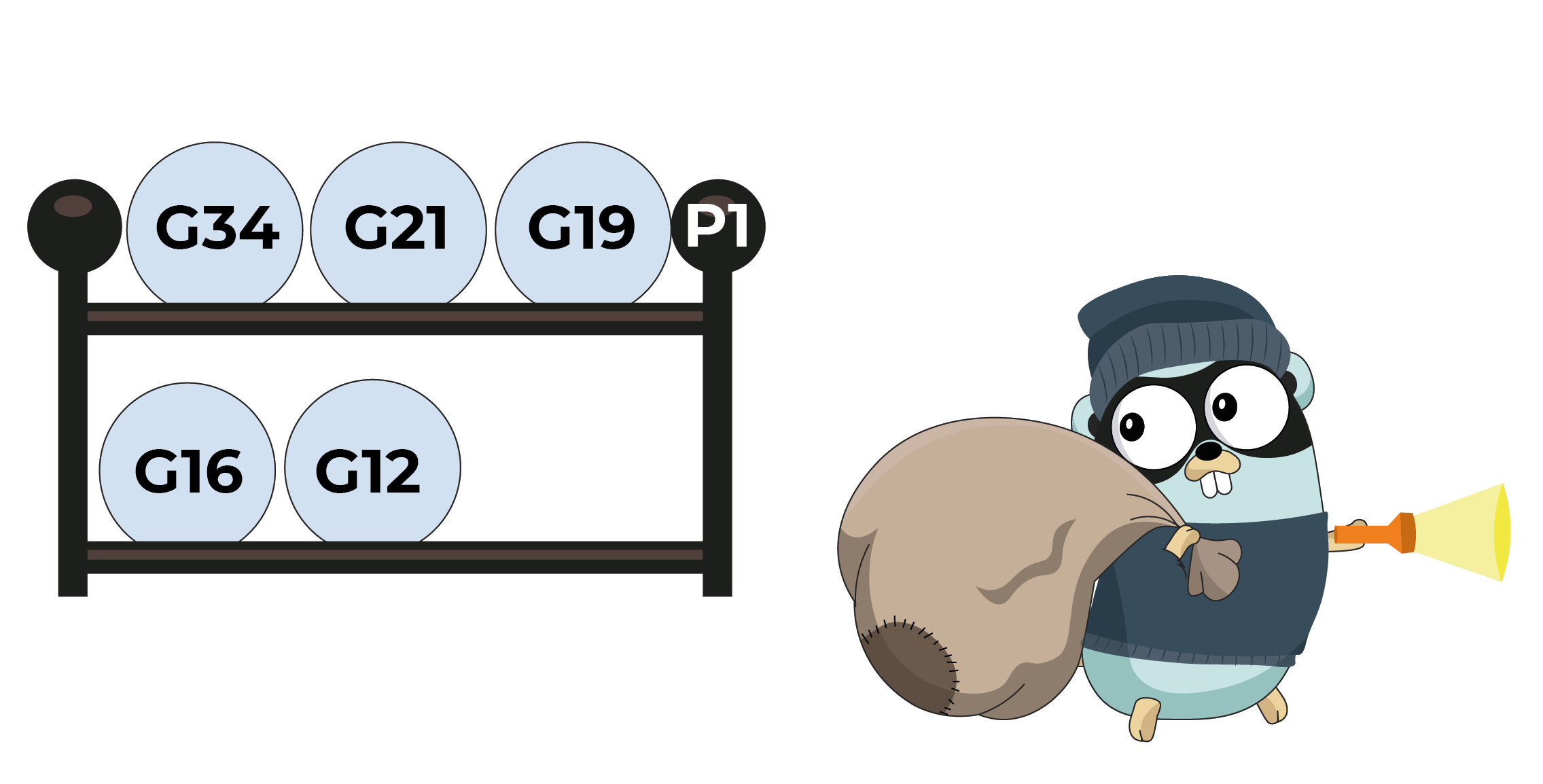

Goroutine stealing

From the perspective of the Go scheduler, the execution of goroutine tasks is a bit fast and some slow. Since my duty is not to let the CPU idle, I must steal some tasks from others to run when I have time.

Quoted from:Go: Work-Stealing in Go Scheduler

There are two queues mentioned earlier, the global/local queue:

- Local queue: refers to the Go goroutine queue (LRQ) associated with the current context P, the local queue, the maximum value of each local goroutine queue in the go1.13 version is 256, more than 256 will be put into the global queue. The local queue can be stolen by other P. In some cases, when a P finds that the local G queue is empty, it will steal other P The local queue of P will steal half of the G from other P’s local queue each time.

- Global queue: In other cases, when there is an idle P and finds that other P local queues have no G to steal, it will try to get the G of the global queue. implement.

runtime.schedule() {

// only 1/61 of the time, check the global runnable queue for a G.

// if not found, check the local queue.

// if not found,

// try to steal from other Ps.

// if not, check the global runnable queue.

// if not found, poll network.

}

The comments above indicate the priority of stealing the various parts, and only 1/61 of the time will go to check the global queue. Priority: local queue > other P’s queue > global queue

At this time, the local queue of P2 is already empty, so at this time P2 is about to steal 3 G from P1

Summary

The idea of Go scheduling is based on the above-mentioned system scheduling. In the final analysis, the goroutine switching in Go is the disconnection and reconnection between P-M-G. Therefore, the switching of the G goroutine in the current thread M is like the switching of the thread on the CPU from the perspective of the system.

Your workload is naturally stopped and this allows a different Goroutine to leverage the same OS/hardware thread efficiently instead of letting the OS/hardware thread sit idle.

Because goroutines are smaller and more lightweight than threads, Go goroutine switching will cost less than OS direct thread switching.

Reference link

Scheduling In Go : Part II - Go Scheduler

Ardanlabs excellent series:

https://www.ardanlabs.com/blog/2018/08/scheduling-in-go-part2.html

dotGo 2017 - JBD - Go’s work stealing scheduler

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yx6FBsGNOp4

Go: Goroutine and Preemption

https://medium.com/a-journey-with-go/go-goroutine-and-preemption-d6bc2aa2f4b7

Go’s work-stealing scheduler

https://rakyll.org/scheduler/