Talk about Go: A high performance pool for reusing object - Sync.Pool

Pooling is frequently occurring in software field, such as connection pool\thread pool\routine poool etc. A pool is essentially to reuse resources.

![]()

Foreword

Pooling is frequently occurring in software field, such as connection pool\thread pool\routine poool etc. A pool is essentially to reuse resources. This time we are going to talk about Go’s offical libary of sync.Pool, and try to understand it’s usage scenarios and internal implementation.

What sync.Pool solved

Let’s talk about the conclusion first. It is a temporary storage and reusable object pool, which is suitable for objects that are frequently applied for and used, and is often used to reduce the burden of GC.

Sync.Pool’s Usage

Common case:

func TestSyncPool(t *testing.T) {

// initialization for mallocating something

mp := &sync.Pool{

New: func() interface{} {

t.Log("create instance")

return 0

}}

ist := mp.Get()

t.Log("ist = ", ist)

ist = 10

// return to pool

mp.Put(ist)

ist = mp.Get()

t.Log("ist = ", ist)

mp.Put(ist)

runtime.GC()

// After executing gc, the object will be temporarily stored in victim.

// That will be explained below. Let's mark it as a garbage can first.

ist = mp.Get()

t.Log("ist = ", ist)

}

Run:

=== RUN TestSyncPool

heypool_test.go:12: create instance

heypool_test.go:17: ist = 0

heypool_test.go:22: ist = 10

heypool_test.go:27: ist = 10 (If the obtained P and the P of the Put() operation are the same, you can still get 10 after the first GC)

--- PASS: TestSyncPool (0.00s)

PASS

It seems to be the same as the regular buffer pool usage, but we look at the comments of the official Get() function,

Get may choose to ignore the pool and treat it as empty.

Callers should not assume any relation between values passed to Put and the values returned by Get.

Here we don’t delve into it first, just look at the comments to tell us that we can’t make association assumptions between put and get operations, we cannot guarantee the GC triggering and the recycling status of the object pool, so sync.Pool is not suitable for scenarios such as database connection pools.

Official example:

This is an official test case, we can further predict the usage intention of sync.Pool

func TestPool(t *testing.T) {

// Temporarily disable system-triggered GC

defer debug.SetGCPercent(debug.SetGCPercent(-1))

var p Pool

if p.Get() != nil {

t.Fatal("expected empty")

}

// Let the running coroutine hang on the current P

// to ensure that the object pool and the program read

// and write one-to-one correspondence

Runtime_procPin()

p.Put("a")

p.Put("b")

if g := p.Get(); g != "a" {

t.Fatalf("got %#v; want a", g)

}

if g := p.Get(); g != "b" {

t.Fatalf("got %#v; want b", g)

}

if g := p.Get(); g != nil {

t.Fatalf("got %#v; want nil", g)

}

Runtime_procUnpin()

for i := 0; i < 100; i++ {

p.Put("c")

}

// Due to the existence of the victim excessive structure,

// the object pool has not been emptied after gc

runtime.GC()

if g := p.Get(); g != "c" {

t.Fatalf("got %#v; want c after GC", g)

}

// From the test code assertion, the second gc will really eliminate them in the victim

runtime.GC()

if g := p.Get(); g != nil {

t.Fatalf("got %#v; want nil after second GC", g)

}

}

Benchmarks

Let’s take a look at the performance comparison before and after the introduction of sync.Pool:

type Pixel struct {

a int

}

var pool = sync.Pool{

New: func() interface{} { return new(Pixel) },

}

//go:noinline

func inc(s *Pixel) { s.a++ }

func BenchmarkWithoutPool(b *testing.B) {

var s *Pixel

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

s = &Pixel{a: 1}

b.StopTimer()

inc(s)

b.StartTimer()

}

}

func BenchmarkWithPool(b *testing.B) {

var s *Pixel

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

s = pool.Get().(*Pixel)

s.a = 1

b.StopTimer()

inc(s)

b.StartTimer()

pool.Put(s)

}

}

Output:

$ go test -bench=.

goos: windows

goarch: amd64

pkg: HelloGo/basic/pool/sync

cpu: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4710MQ CPU @ 2.50GHz

BenchmarkWithoutPool-8 4817011 271.9 ns/op

BenchmarkWithPool-8 12893811 107.9 ns/op

PASS

ok HelloGo/basic/pool/sync 472.933s

How Sync.Pool be designed

Before exploring the internal implementation, let’s extract some concepts.

1.GMP cooperation

We all know the GMP model of coroutine scheduling in Go(可参考专栏之前的总结笔记:聊一聊操作系统线程调度与Go协程), each processing core P has its own coroutine G task queue, the underlying Get() object acquisition function of sync.Pool is obtained through local private queues and shared queues.

func (p *Pool) Get() interface{} {

if race.Enabled {

race.Disable()

}

// Specify the currently accessed P to

// ensure that it is in the same object pool

l, pid := p.pin()

x := l.private

l.private = nil

if x == nil {

// If the current private queue is empty, try popping from the shared pool

x, _ = l.shared.popHead()

if x == nil {

// If the shared pool is empty, go to other P pools to steal

x = p.getSlow(pid)

}

}

runtime_procUnpin()

if race.Enabled {

race.Enable()

if x != nil {

race.Acquire(poolRaceAddr(x))

}

}

// If the private space is empty, and the steal is empty,

// call the initialization to construct the object

if x == nil && p.New != nil {

x = p.New()

}

return x

}

2.multilevel cache

In the operating system components, start from CPU registers to physical disks, and from one CPU cycle to L1/2/3 cache, to main memory, and then to the file system, the magnitude of the operation time for a single access is increasing. The idea of caching was introduced very early in the computer field.

As hardware architecture and technology advanced, processor performance and frequency grew much faster than memory cycle times, leading to a large gap in performance. The problem of increasing memory latency, relative to processor speed, has been dealt with by adding high speed cache memory.

Let’s take a look at the internal members of sync.Pool:

type Pool struct {

noCopy noCopy

local unsafe.Pointer // the object address specified by the current P

localSize uintptr // size of the local array

victim unsafe.Pointer // the transition interval for the first elimination of the current P

victimSize uintptr // size of victims array

New func() interface{}

}

Through the victim sacrifice pool, the objects that are reclaimed for the first time are temporarily stored, so that the program can reuse as much as possible before applying for objects, and it is more “smoothly” to use.

func init() {

// sync.Pool starts the registered GC execution logic

runtime_registerPoolCleanup(poolCleanup)

}

func poolCleanup() {

// When GC triggers execution, clear the old object pool of the recycle bin

for _, p := range oldPools {

p.victim = nil

p.victimSize = 0

}

// temporarily store objects to be eliminated in victim

for _, p := range allPools {

p.victim = p.local

p.victimSize = p.localSize

p.local = nil

p.localSize = 0

}

oldPools, allPools = allPools, nil

}

Registering the GC processing logic at startup, you can see that the ``victim``` mechanism actually draws on the idea of generational recycling in other languages, and will temporarily store objects before cleaning up, improving the probability of reuse.

After the above dismantling, we can know that the priority is obtained in the object pools of multiple Ps, as shown in the following figure:

![]()

It can be seen that since each P is independent, ① private pool, ② sacrifice pool, and ⑤ initial creation are exclusive to the current P, and only ③ may be shared by other P, so about step ③ sharing operation requires locking.

3.Lock-free

Let’s take a look at how Sync.Pool is handled step ③

func (d *poolDequeue) popHead() (interface{}, bool) {

var slot *eface

for {

// Get the atomic variable to determine the range of the current shared queue

ptrs := atomic.LoadUint64(&d.headTail)

head, tail := d.unpack(ptrs)

if tail == head {

return nil, false

}

head--

ptrs2 := d.pack(head, tail)

if atomic.CompareAndSwapUint64(&d.headTail, ptrs, ptrs2) {

// Spinlock design based on optimistic expectations using CAS

slot = &d.vals[head&uint32(len(d.vals)-1)]

// Jump out after obtaining the right to execute

break

}

}

// ...

return val, true

}

By using the optimistically expected spin lock, it is more lightweight than the read-write lock, and achieves a nearly lock-free design.

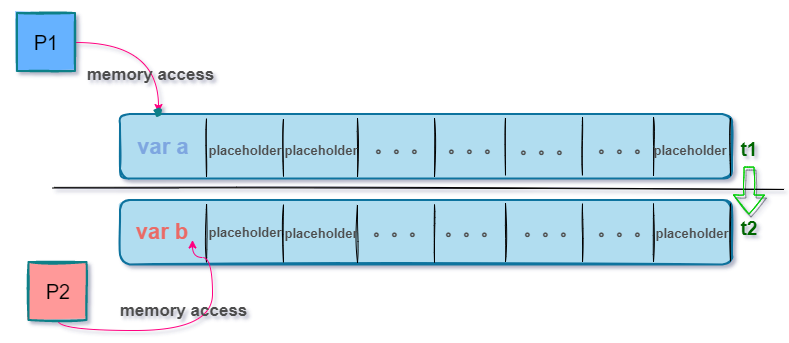

4.false sharing

The fourth concept is about false sharing. What is false sharing? In fact, it means that when we want to update the value of a variable, when the CPU reads and loads the memory block (row loading), due to the principle of local access, it is looking for When the address space is continuous, when the variable is loaded for operation, it will cover the address space of other variables at the same time.

At this time, each P should consider whether my variable is affected by the continuous interval of other variables, Because in the same address space, there will be conflicts when there are concurrent reads and writes, as shown in the following figure:

![]()

In order to avoid it, there are two processing methods that can be thought of:

-

exclusive mutual exclusion: That is to say, only one P is guaranteed to operate at a time, and the exclusive processing has a great impact on performance.

-

memory alignment: Using padding bits, when storing variables, fill in placeholders for the continuous address space to ensure that the variable range of the current operation is consistent with the instruction addressing space, that is, there is no need to worry about other variable address out-of-bounds issues.

Personally, I think the second method is more in line with the philosophy of Go concurrency:Don’t use shared memory to communicate, use communication to share memory.

How does it work in sync.Pool?

// Local per-P Pool appendix.

type poolLocalInternal struct {

private interface{} // Private P flag

shared poolChain // The queue pointed to by the local P

}

type poolLocal struct {

poolLocalInternal

// Fill the byte array and use multiples of 128 to access the address range

pad [128 - unsafe.Sizeof(poolLocalInternal{})%128]byte

}

It can be seen that poolLocal has an internal member of pad, of which poolLocal is actually the memory block pointed to by the internal local pointer of sync.Pool. 128 size range (a multiple of 64-bit system) to access, each time the object pool addressing is consistent with the CPU single instruction operation range, so as to avoid the “false sharing problem”, as shown in the figure above.

Summary

Above, we analyzed Sync.Pool from the concepts of GMP model, multi-level cache, false sharing, etc., to know its internal acquisition priority, and how it solves multiple P Conflicts, and use CAS to reduce the burden of lock operations.

It can be felt that Go is silently following certain design specifications, both in terms of macro and detailed implementation.

Reference link

- Explore Go sync.Pool as Cache

https://medium.com/geekculture/go-sync-pool-as-cache-in-kubernetes-4e247c52e732 - 深度分析 Golang sync.Pool 底层原理

https://www.cyhone.com/articles/think-in-sync-pool/ - Go: Understand the Design of Sync.Pool

https://medium.com/a-journey-with-go/go-understand-the-design-of-sync-pool-2dde3024e277